What

A textual description (i.e. prose) can be used to describe requirements. Prose is especially useful when describing abstract ideas such as the vision of a product.

The product vision of the TEAMMATES Project given below is described using prose.

TEAMMATES aims to become the biggest student project in the world (biggest here refers to 'many contributors, many users, large code base, evolving over a long period'). Furthermore, it aims to serve as a training tool for Software Engineering students who want to learn SE skills in the context of a non-trivial real software product.

Avoid using lengthy prose to describe requirements; they can be hard to follow.

What

Feature list: A list of features of a product grouped according to some criteria such as aspect, priority, order of delivery, etc.

A sample feature list from a simple Minesweeper game (only a brief description has been provided to save space):

- Basic play – Single player play.

- Difficulty levels

- Medium levels

- Advanced levels

- Versus play – Two players can play against each other.

- Timer – Additional fixed time restriction on the player.

- ...

Introduction

User story: User stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the new capability, usually a user or customer of the system. [Mike Cohn]

A common format for writing user stories is:

User story format: As a {user type/role} I can {function} so that {benefit}

Examples (from a Learning Management System):

- As a student, I can download files uploaded by lecturers, so that I can get my own copy of the files

- As a lecturer, I can create discussion forums, so that students can discuss things online

- As a tutor, I can print attendance sheets, so that I can take attendance during the class

You can write user stories on index cards or sticky notes, and arrange them on walls or tables, to facilitate planning and discussion. Alternatively, you can use a software (e.g., GitHub Project Boards, Trello, Google Docs, ...) to manage user stories digitally.

Details

The {benefit} can be omitted if it is obvious.

As a user, I can login to the system so that I can access my data

It is recommended to confirm there is a concrete benefit even if you omit it from the user story. If not, you could end up adding features that have no real benefit.

You can add more characteristics to the {user role} to provide more context to the user story.

- As a forgetful user, I can view a password hint, so that I can recall my password.

- As an expert user, I can tweak the underlying formatting tags of the document, so that I can format the document exactly as I need.

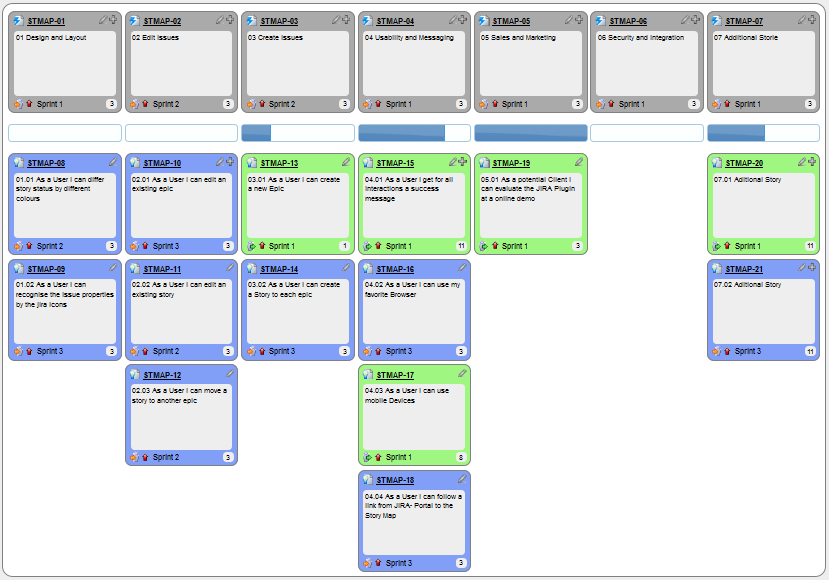

You can write user stories at various levels. High-level user stories, called epics (or themes) cover bigger functionality. You can then break down these epics to multiple user stories of normal size.

[Epic] As a lecturer, I can monitor student participation levels

- As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student

so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum - As a lecturer, I can view webcast view records of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not view webcasts - As a lecturer, I can view file download statistics of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not download lecture materials

You can add conditions of satisfaction to a user story to specify things that need to be true for the user story implementation to be accepted as ‘done’.

As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum.

Conditions:

Separate post count for each forum should be shown

Total post count of a student should be shown

The list should be sortable by student name and post count

Other useful info that can be added to a user story includes (but not limited to)

- Priority: how important the user story is

- Size: the estimated effort to implement the user story

- Urgency: how soon the feature is needed

Usage

User stories capture user requirements in a way that is convenient for , , and .

[User stories] strongly shift the focus from writing about features to discussing them. In fact, these discussions are more important than whatever text is written. [Mike Cohn, MountainGoat Software 🔗]

User stories differ from mainly in the level of detail. User stories should only provide enough details to make a reasonably low risk estimate of how long the user story will take to implement. When the time comes to implement the user story, the developers will meet with the customer face-to-face to work out a more detailed description of the requirements. [more...]

User stories can capture non-functional requirements too because even NFRs must benefit some stakeholder.

An example of an NFR captured as a user story:

| As a | I want to | so that |

|---|---|---|

| impatient user | to be able experience reasonable response time from the website while up to 1000 concurrent users are using it | I can use the app even when the traffic is at the maximum expected level |

Given their lightweight nature, user stories are quite handy for recording requirements during early stages of requirements gathering.

A recipe for brainstorming user stories

Given below is a possible recipe you can take when using user stories for early stages of requirement gathering.

Step 0: Clear your mind of preconceived product ideas

Even if you already have some idea of what your product will look/behave like in the end, clear your mind of those ideas. The product is the solution. At this point, we are still at the stage of figuring out the problem (i.e., user requirements). Let's try to get from the problem to the solution in a systematic way, one step at a time.

Step 1: Define the target user as a persona:

Decide your target user's profile (e.g. a student, office worker, programmer, salesperson) and work patterns (e.g. Does he work in groups or alone? Does he share his computer with others?). A clear understanding of the target user will help when deciding the importance of a user story. You can even narrow it down to a persona. Here is an example:

Jean is a university student studying in a non-IT field. She interacts with a lot of people due to her involvement in university clubs/societies. ...

Step 2: Define the problem scope:

Decide the exact problem you are going to solve for the target user. It is also useful to specify what related problems it will not solve so that the exact scope is clear.

ProductX helps Jean keep track of all her school contacts. It does not cover communicating with contacts.

Step 3: List scenarios to form a narrative:

Think of the various scenarios your target user is likely to go through as she uses your app. Following a chronological sequence as if you are telling a story might be helpful.

A. First use:

- Jean gets to know about ProductX. She downloads it and launches it to check out what it can do.

- After playing around with the product for a bit, Jean wants to start using it for real.

- ...

B. Second use: (Jean is still a beginner)

- Jean launches ProductX. She wants to find ...

- ...

C. 10th use: (Jean is a little bit familiar with the app)

- ...

D. 100th use: (Jean is an expert user)

- Jean launches the app and does ... and ... followed by ... as per her usual habit.

- Jean feels some of the data in the app are no longer needed. She wants to get rid of them to reduce clutter.

More examples that might apply to some products:

- Jean uses the app at the start of the day to ...

- Jean uses the app before going to sleep to ...

- Jean hasn't used the app for a while because she was on a three-month training programme. She is now back at work and wants to resume her daily use of the app.

- Jean moves to another company. Some of her clients come with her but some don't.

- Jean starts freelancing in her spare time. She wants to keep her freelancing clients separate from her other clients.

Step 4: List the user stories to support the scenarios:

Based on the scenarios, decide on the user stories you need to support. For example, based on the scenario 'A. First use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As a potential user exploring the app, I can see the app populated with sample data, so that I can easily see how the app will look like when it is in use.

- As a user ready to start using the app, I can purge all current data, so that I can get rid of sample/experimental data I used for exploring the app.

To give another example, based on the scenario 'D. 100th use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As an expert user, I can create shortcuts for tasks, so that I can save time on frequently performed tasks.

- As a long-time user, I can archive/hide unused data, so that I am not distracted by irrelevant data.

Do not 'evaluate' the value of user stories while brainstorming. Reason: an important aspect of brainstorming is not judging the ideas generated.

Other tips:

- Don't be too hasty to discard 'unusual' user stories:

Those might make your product unique and stand out from the rest, at least for the target users. - Don't go into too much detail:

For example, consider this user story:

As a user, I want to see a list of tasks that need my attention most at the present time, so that I pay attention to them first.

When discussing this user story, don't worry about what tasks should be considered 'needs my attention most at the present time'. Those details can be worked out later. - Don't be biased by preconceived product ideas:

When you are at the stage of identifying user needs, clear your mind of ideas you have about what your end product will look like. That is, don't try to reverse-engineer a preconceived product idea into user stories. - Don't discuss implementation details or whether you are actually going to implement it:

When gathering requirements, your decision is whether the user's need is important enough for you to want to fulfil it. Implementation details can be discussed later. If a user story turns out to be too difficult to implement later, you can always omit it from the implementation plan.

While use cases can be recorded on in the initial stages, an online tool is more suitable for longer-term management of user stories, especially if the team is not .

Introduction

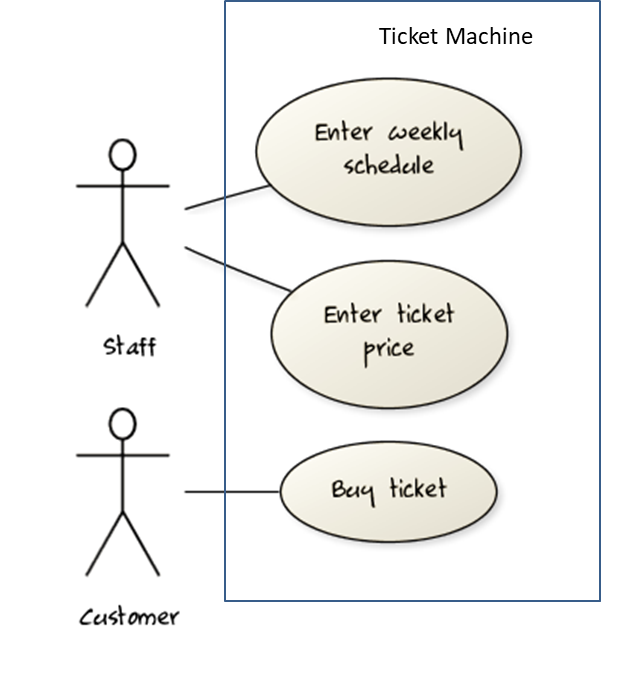

Use case: A description of a set of sequences of actions, including variants, that a system performs to yield an observable result of value to an actor [ 📖 : ].

A use case describes an interaction between the user and the system for a specific functionality of the system.

UML includes a diagram type called use case diagrams that can illustrate use cases of a system visually, providing a visual ‘table of contents’ of the use cases of a system.

In the example on the right, note how use cases are shown as ovals and user roles relevant to each use case are shown as stick figures connected to the corresponding ovals.

Use cases capture the functional requirements of a system.

What

Glossary: A glossary serves to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the noteworthy terms, abbreviations, acronyms etc.

Here is a partial glossary from a variant of the Snakes and Ladders game:

- Conditional square: A square that specifies a specific face value which a player has to throw before his/her piece can leave the square.

- Normal square: a normal square does not have any conditions, snakes, or ladders in it.