Week 9 [Mon, Mar 13th] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Let's learn about the requirements aspect of SE projects. Although you have already started your module project (which didn't require heavy work on the requirements aspect), it is good to learn more about this topic, so that you can use it in future projects.

Can explain requirements

A software requirement specifies a need to be fulfilled by the software product.

A software project may be,

- a brownfield project i.e., develop a product to replace/update an existing software product

- a greenfield project i.e., develop a totally new system with no precedent

In either case, requirements need to be gathered, analyzed, specified, and managed.

Requirements come from stakeholders.

Stakeholder: A party that is potentially affected by the software project. e.g. users, sponsors, developers, interest groups, government agencies, etc.

Identifying requirements is often not easy. For example, stakeholders may not be aware of their precise needs, may not know how to communicate their requirements correctly, may not be willing to spend effort in identifying requirements, etc.

Can explain non-functional requirements

Requirements can be divided into two in the following way:

- Functional requirements specify what the system should do.

- Non-functional requirements specify the constraints under which the system is developed and operated.

Some examples of non-functional requirement categories:

- Data requirements e.g. size, , etc.,

- Environment requirements e.g. technical environment in which the system would operate in or needs to be compatible with.

- Accessibility, Capacity, Compliance with regulations, Documentation, Disaster recovery, Efficiency, Extensibility, Fault tolerance, Interoperability, Maintainability, Privacy, Portability, Quality, Reliability, Response time, Robustness, Scalability, Security, Stability, Testability, and more ...

Some concrete examples of NFRs

- Business/domain rules: e.g. the size of the minefield cannot be smaller than five.

- Constraints: e.g. the system should be backward compatible with data produced by earlier versions of the system; system testers are available only during the last month of the project; the total project cost should not exceed $1.5 million.

- Technical requirements: e.g. the system should work on both 32-bit and 64-bit environments.

- Performance requirements: e.g. the system should respond within two seconds.

- Quality requirements: e.g. the system should be usable by a novice who has never carried out an online purchase.

- Process requirements: e.g. the project is expected to adhere to a schedule that delivers a feature set every one month.

- Notes about project scope: e.g. the product is not required to handle the printing of reports.

- Any other noteworthy points: e.g. the game should not use images deemed offensive to those injured in real mine clearing activities.

You may have to spend an extra effort in digging NFRs out as early as possible because,

- NFRs are easier to miss e.g., stakeholders tend to think of functional requirements first

- sometimes NFRs are critical to the success of the software. E.g. A web application that is too slow or that has low security is unlikely to succeed even if it has all the right functionality.

Exercises

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next, a quick look at techniques used for gathering requirements. They are mostly common-sense but let's go through them for completeness' sake anyway.

Can explain brainstorming

Brainstorming: A group activity designed to generate a large number of diverse and creative ideas for the solution of a problem.

In a brainstorming session there are no "bad" ideas. The aim is to generate ideas; not to validate them. Brainstorming encourages you to "think outside the box" and put "crazy" ideas on the table without fear of rejection.

Exercises

Can explain product surveys

Studying existing products can unearth shortcomings of existing solutions that can be addressed by a new product. Product manuals and other forms of documentation of an existing system can tell us how the existing solutions work.

When developing a game for a mobile device, a look at a similar PC game can give insight into the kind of features and interactions the mobile game can offer.

Can explain observation

Observing users in their natural work environment can uncover product requirements. Usage data of an existing system can also be used to gather information about how an existing system is being used, which can help in building a better replacement e.g. to find the situations where the user makes mistakes when using the current system.

Can explain focus groups

[source]

Focus groups are a kind of informal interview within an interactive group setting. A group of people (e.g. potential users, beta testers) are asked about their understanding of a specific issue, process, product, advertisement, etc.

Can explain prototyping

Prototype: A prototype is a mock up, a scaled down version, or a partial system constructed

- to get users’ feedback.

- to validate a technical concept (a "proof-of-concept" prototype).

- to give a preview of what is to come, or to compare multiple alternatives on a small scale before committing fully to one alternative.

- for early field-testing under controlled conditions.

Prototyping can uncover requirements, in particular, those related to how users interact with the system. UI prototypes or mock ups are often used in brainstorming sessions, or in meetings with the users to get quick feedback from them.

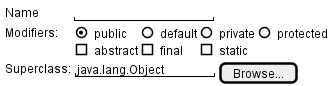

A mock up (also called a wireframe diagram) of a dialog box:

[source: plantuml.com]

Prototyping can be used for discovering as well as specifying requirements e.g. a UI prototype can serve as a specification of what to build.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you may have noticed in the section about prototyping, some techniques can be used for both gathering and specifying requirements. The two things often go hand-in-hand any way. For example, you gather some requirements, specify them in some form, and show them to stakeholders to get feedback.

Now, let's look at other techniques used for specifying requirements.

Prose

Can explain prose

A textual description (i.e. prose) can be used to describe requirements. Prose is especially useful when describing abstract ideas such as the vision of a product.

The product vision of the TEAMMATES Project given below is described using prose.

TEAMMATES aims to become the biggest student project in the world (biggest here refers to 'many contributors, many users, large code base, evolving over a long period'). Furthermore, it aims to serve as a training tool for Software Engineering students who want to learn SE skills in the context of a non-trivial real software product.

Avoid using lengthy prose to describe requirements; they can be hard to follow.

Feature Lists

Can explain feature list

Feature list: A list of features of a product grouped according to some criteria such as aspect, priority, order of delivery, etc.

A sample feature list from a simple Minesweeper game (only a brief description has been provided to save space):

- Basic play – Single player play.

- Difficulty levels

- Medium levels

- Advanced levels

- Versus play – Two players can play against each other.

- Timer – Additional fixed time restriction on the player.

- ...

User Stories

Can write simple user stories

User story: User stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the new capability, usually a user or customer of the system. [Mike Cohn]

A common format for writing user stories is:

User story format: As a {user type/role} I can {function} so that {benefit}

Examples (from a Learning Management System):

- As a student, I can download files uploaded by lecturers, so that I can get my own copy of the files

- As a lecturer, I can create discussion forums, so that students can discuss things online

- As a tutor, I can print attendance sheets, so that I can take attendance during the class

You can write user stories on index cards or sticky notes, and arrange them on walls or tables, to facilitate planning and discussion. Alternatively, you can use a software (e.g., GitHub Project Boards, Trello, Google Docs, ...) to manage user stories digitally.

User stories in use

With sticky notes

With paper

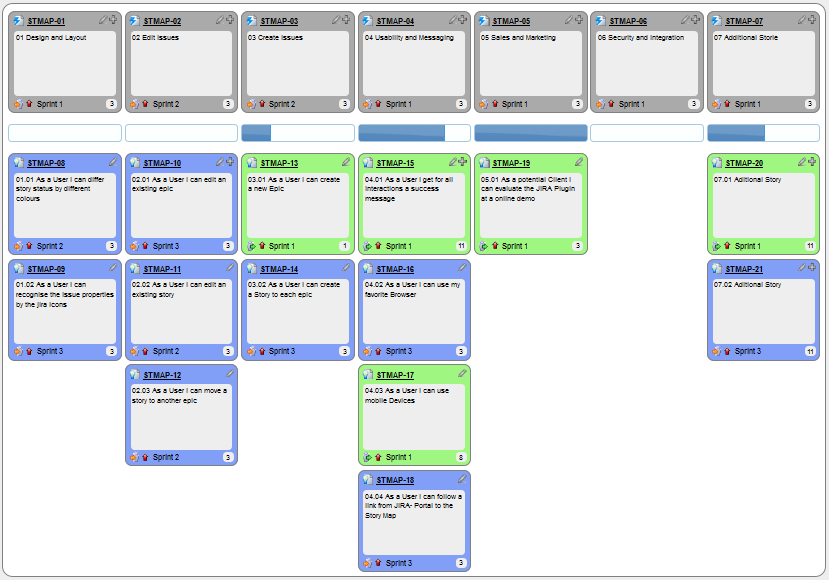

With software

Exercises

Can write more detailed user stories

The {benefit} can be omitted if it is obvious.

As a user, I can login to the system so that I can access my data

It is recommended to confirm there is a concrete benefit even if you omit it from the user story. If not, you could end up adding features that have no real benefit.

You can add more characteristics to the {user role} to provide more context to the user story.

- As a forgetful user, I can view a password hint, so that I can recall my password.

- As an expert user, I can tweak the underlying formatting tags of the document, so that I can format the document exactly as I need.

You can write user stories at various levels. High-level user stories, called epics (or themes) cover bigger functionality. You can then break down these epics to multiple user stories of normal size.

[Epic] As a lecturer, I can monitor student participation levels

- As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student

so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum - As a lecturer, I can view webcast view records of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not view webcasts - As a lecturer, I can view file download statistics of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not download lecture materials

You can add conditions of satisfaction to a user story to specify things that need to be true for the user story implementation to be accepted as ‘done’.

As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum.

Conditions:

Separate post count for each forum should be shown

Total post count of a student should be shown

The list should be sortable by student name and post count

Other useful info that can be added to a user story includes (but not limited to)

- Priority: how important the user story is

- Size: the estimated effort to implement the user story

- Urgency: how soon the feature is needed

Exercises

Can use user stories to manage requirements of project

User stories capture user requirements in a way that is convenient for , , and .

[User stories] strongly shift the focus from writing about features to discussing them. In fact, these discussions are more important than whatever text is written. [Mike Cohn, MountainGoat Software 🔗]

User stories differ from mainly in the level of detail. User stories should only provide enough details to make a reasonably low risk estimate of how long the user story will take to implement. When the time comes to implement the user story, the developers will meet with the customer face-to-face to work out a more detailed description of the requirements. [more...]

User stories can capture non-functional requirements too because even NFRs must benefit some stakeholder.

An example of an NFR captured as a user story:

| As a | I want to | so that |

|---|---|---|

| impatient user | to be able experience reasonable response time from the website while up to 1000 concurrent users are using it | I can use the app even when the traffic is at the maximum expected level |

Given their lightweight nature, user stories are quite handy for recording requirements during early stages of requirements gathering.

A recipe for brainstorming user stories

Given below is a possible recipe you can take when using user stories for early stages of requirement gathering.

Step 0: Clear your mind of preconceived product ideas

Even if you already have some idea of what your product will look/behave like in the end, clear your mind of those ideas. The product is the solution. At this point, we are still at the stage of figuring out the problem (i.e., user requirements). Let's try to get from the problem to the solution in a systematic way, one step at a time.

Step 1: Define the target user as a persona:

Decide your target user's profile (e.g. a student, office worker, programmer, salesperson) and work patterns (e.g. Does he work in groups or alone? Does he share his computer with others?). A clear understanding of the target user will help when deciding the importance of a user story. You can even narrow it down to a persona. Here is an example:

Jean is a university student studying in a non-IT field. She interacts with a lot of people due to her involvement in university clubs/societies. ...

Step 2: Define the problem scope:

Decide the exact problem you are going to solve for the target user. It is also useful to specify what related problems it will not solve so that the exact scope is clear.

ProductX helps Jean keep track of all her school contacts. It does not cover communicating with contacts.

Step 3: List scenarios to form a narrative:

Think of the various scenarios your target user is likely to go through as she uses your app. Following a chronological sequence as if you are telling a story might be helpful.

A. First use:

- Jean gets to know about ProductX. She downloads it and launches it to check out what it can do.

- After playing around with the product for a bit, Jean wants to start using it for real.

- ...

B. Second use: (Jean is still a beginner)

- Jean launches ProductX. She wants to find ...

- ...

C. 10th use: (Jean is a little bit familiar with the app)

- ...

D. 100th use: (Jean is an expert user)

- Jean launches the app and does ... and ... followed by ... as per her usual habit.

- Jean feels some of the data in the app are no longer needed. She wants to get rid of them to reduce clutter.

More examples that might apply to some products:

- Jean uses the app at the start of the day to ...

- Jean uses the app before going to sleep to ...

- Jean hasn't used the app for a while because she was on a three-month training programme. She is now back at work and wants to resume her daily use of the app.

- Jean moves to another company. Some of her clients come with her but some don't.

- Jean starts freelancing in her spare time. She wants to keep her freelancing clients separate from her other clients.

Step 4: List the user stories to support the scenarios:

Based on the scenarios, decide on the user stories you need to support. For example, based on the scenario 'A. First use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As a potential user exploring the app, I can see the app populated with sample data, so that I can easily see how the app will look like when it is in use.

- As a user ready to start using the app, I can purge all current data, so that I can get rid of sample/experimental data I used for exploring the app.

To give another example, based on the scenario 'D. 100th use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As an expert user, I can create shortcuts for tasks, so that I can save time on frequently performed tasks.

- As a long-time user, I can archive/hide unused data, so that I am not distracted by irrelevant data.

Do not 'evaluate' the value of user stories while brainstorming. Reason: an important aspect of brainstorming is not judging the ideas generated.

Other tips:

- Don't be too hasty to discard 'unusual' user stories:

Those might make your product unique and stand out from the rest, at least for the target users. - Don't go into too much detail:

For example, consider this user story:

As a user, I want to see a list of tasks that need my attention most at the present time, so that I pay attention to them first.

When discussing this user story, don't worry about what tasks should be considered 'needs my attention most at the present time'. Those details can be worked out later. - Don't be biased by preconceived product ideas:

When you are at the stage of identifying user needs, clear your mind of ideas you have about what your end product will look like. That is, don't try to reverse-engineer a preconceived product idea into user stories. - Don't discuss implementation details or whether you are actually going to implement it:

When gathering requirements, your decision is whether the user's need is important enough for you to want to fulfil it. Implementation details can be discussed later. If a user story turns out to be too difficult to implement later, you can always omit it from the implementation plan.

While use cases can be recorded on in the initial stages, an online tool is more suitable for longer-term management of user stories, especially if the team is not .

Tool Examples: How to use some example online tools to manage user stories

Resources

- This article by Mike Cohn from MountainGoatSoftware explains how to use user stories to capture NFRs.

Use Cases

Can explain use cases

Use case: A description of a set of sequences of actions, including variants, that a system performs to yield an observable result of value to an actor [ 📖 : ].

A use case describes an interaction between the user and the system for a specific functionality of the system.

Example 1: 'transfer money' use case for an online banking system

System: Online Banking System (OBS) Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money Actor: User MSS: 1. User chooses to transfer money. 2. OBS requests for details of the transfer. 3. User enters the requested details. 4. OBS requests for confirmation. 5. User confirms. 6. OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance. Use case ends.

Extensions:

3a. OBS detects an error in the entered data.

3a1. OBS requests for the correct data.

3a2. User enters new data.

Steps 3a1-3a2 are repeated until the data entered are correct.

Use case resumes from step 4.

3b. User requests to effect the transfer in a future date.

3b1. OBS requests for confirmation.

3b2. User confirms future transfer.

Use case ends.

*a. At any time, User chooses to cancel the transfer.

*a1. OBS requests to confirm the cancellation.

*a2. User confirms the cancellation.

Use case ends.

Example 2: 'upload file' use case of an LMS

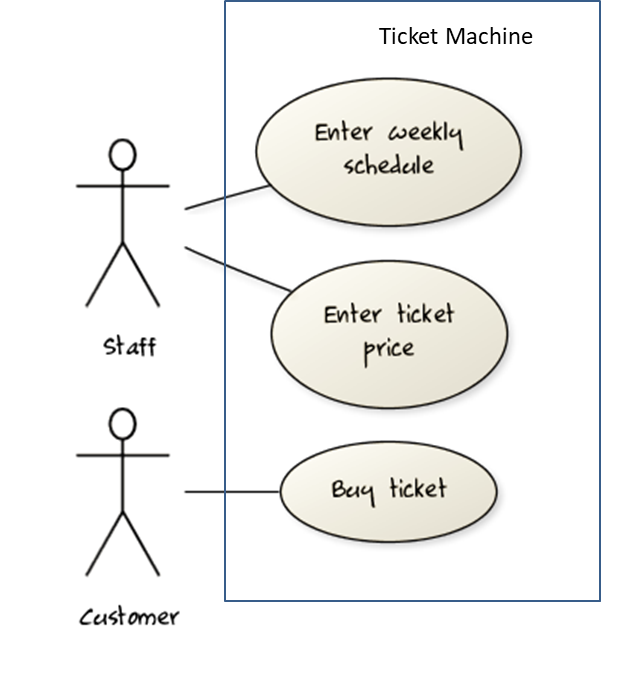

UML includes a diagram type called use case diagrams that can illustrate use cases of a system visually, providing a visual ‘table of contents’ of the use cases of a system.

In the example on the right, note how use cases are shown as ovals and user roles relevant to each use case are shown as stick figures connected to the corresponding ovals.

Use cases capture the functional requirements of a system.

Glossary

Can explain glossary

Glossary: A glossary serves to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the noteworthy terms, abbreviations, acronyms etc.

Here is a partial glossary from a variant of the Snakes and Ladders game:

- Conditional square: A square that specifies a specific face value which a player has to throw before his/her piece can leave the square.

- Normal square: a normal square does not have any conditions, snakes, or ladders in it.

Supplementary Requirements

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As your project gets bigger and changes become more frequent, it's natural to look for ways to automate the many steps involved in going from the code you write in the editor to an executable product. This is a good time to start learning about that aspect too.

Can explain build automation tools

Build automation tools automate the steps of the build process, usually by means of build scripts.

In a non-trivial project, building a product from its source code can be a complex multi-step process. For example, it can include steps such as: pull code from the revision control system, compile, link, run automated tests, automatically update release documents (e.g. build number), package into a distributable, push to repo, deploy to a server, delete temporary files created during building/testing, email developers of the new build, and so on. Furthermore, this build process can be done ‘on demand’, it can be scheduled (e.g. every day at midnight) or it can be triggered by various events (e.g. triggered by a code push to the revision control system).

Some of these build steps such as compiling, linking and packaging, are already automated in most modern IDEs. For example, several steps happen automatically when the ‘build’ button of the IDE is clicked. Some IDEs even allow customization of this build process to some extent.

However, most big projects use specialized build tools to automate complex build processes.

Some popular build tools relevant to Java developers: Gradle, Maven, Apache Ant, GNU Make

Some other build tools: Grunt (JavaScript), Rake (Ruby)

Some build tools also serve as dependency management tools. Modern software projects often depend on third party libraries that evolve constantly. That means developers need to download the correct version of the required libraries and update them regularly. Therefore, dependency management is an important part of build automation. Dependency management tools can automate that aspect of a project.

Maven and Gradle, in addition to managing the build process, can play the role of dependency management tools too.

Resources

- Getting Started with Gradle -- documentation from Gradle

- Gradle Tutorial -- from tutorialspoint.com

Working With Gradle in Intellij IDEA (6 minutes)

Exercises

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Soon, you will start writing automated Java tests for your project.

First, let us learn such testing fits into an aspect called developer testing of the testing landscape.

Can explain the need for early developer testing

Delaying testing until the full product is complete has a number of disadvantages:

- Locating the cause of a test case failure is difficult due to a large search space; in a large system, the search space could be millions of lines of code, written by hundreds of developers! The failure may also be due to multiple inter-related bugs.

- Fixing a bug found during such testing could result in major rework, especially if the bug originated from the design or during requirements specification i.e. a faulty design or faulty requirements.

- One bug might 'hide' other bugs, which could emerge only after the first bug is fixed.

- The delivery may have to be delayed if too many bugs are found during testing.

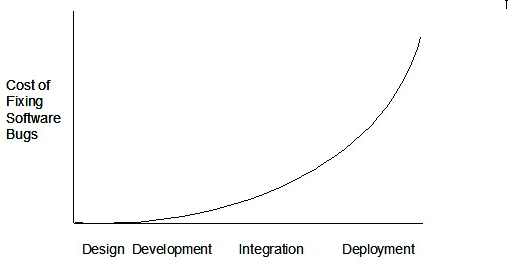

Therefore, it is better to do early testing, as hinted by the popular rule of thumb given below, also illustrated by the graph below it.

The earlier a bug is found, the easier and cheaper to have it fixed.

Such early testing of partially developed software is usually, and by necessity, done by the developers themselves i.e. developer testing.

Exercises

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Unit testing is the type of developer testing that is used the most. Let's learn about it next.

Can explain test drivers

A test driver is the code that ‘drives’ the for the purpose of testing i.e. invoking the SUT with test inputs and verifying if the behavior is as expected.

PayrollTest ‘drives’ the Payroll class by sending it test inputs and verifies if the output is as expected.

public class PayrollTest {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

// test setup

Payroll p = new Payroll();

// test case 1

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001", "E002"});

// automatically verify the response

if (p.totalSalary() != 6400) {

throw new Error("case 1 failed ");

}

// test case 2

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001"});

if (p.totalSalary() != 2300) {

throw new Error("case 2 failed ");

}

// more tests...

System.out.println("All tests passed");

}

}

Can explain test automation tools

JUnit is a tool for automated testing of Java programs. Similar tools are available for other languages and for automating different types of testing.

This is an automated test for a Payroll class, written using JUnit libraries.

@Test

public void testTotalSalary() {

Payroll p = new Payroll();

// test case 1

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001", "E002"});

assertEquals(6400, p.totalSalary());

// test case 2

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001"});

assertEquals(2300, p.totalSalary());

// more tests...

}

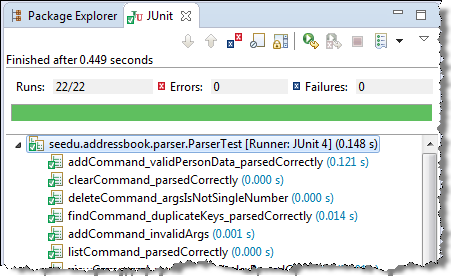

Most modern IDEs have integrated support for testing tools. The figure below shows the JUnit output when running some JUnit tests using the Eclipse IDE.

Can explain unit testing

Unit testing: testing individual units (methods, classes, subsystems, ...) to ensure each piece works correctly.

In OOP code, it is common to write one or more unit tests for each public method of a class.

Here are the code skeletons for a Foo class containing two methods and a FooTest class that contains unit tests for those two methods.

class Foo {

String read() {

// ...

}

void write(String input) {

// ...

}

}

class FooTest {

@Test

void read() {

// a unit test for Foo#read() method

}

@Test

void write_emptyInput_exceptionThrown() {

// a unit tests for Foo#write(String) method

}

@Test

void write_normalInput_writtenCorrectly() {

// another unit tests for Foo#write(String) method

}

}

import unittest

class Foo:

def read(self):

# ...

def write(self, input):

# ...

class FooTest(unittest.TestCase):

def test_read(self):

# a unit test for read() method

def test_write_emptyIntput_ignored(self):

# a unit test for write(string) method

def test_write_normalInput_writtenCorrectly(self):

# another unit test for write(string) method

Resources

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Now, let us learn about JUnit, a tool used for automated testing. JUnit is a third-party tool (not included in the JDK).

Can use simple JUnit tests

When writing JUnit tests for a class Foo, the common practice is to create a FooTest class, which will contain various test methods.

Suppose we want to write tests for the IntPair class below.

public class IntPair {

int first;

int second;

public IntPair(int first, int second) {

this.first = first;

this.second = second;

}

public int intDivision() throws Exception {

if (second == 0){

throw new Exception("Divisor is zero");

}

return first/second;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return first + "," + second;

}

}

Here's a IntPairTest class to match (using JUnit 5).

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.fail;

public class IntPairTest {

@Test

public void testStringConversion() {

assertEquals("4,7", new IntPair(4, 7).toString());

}

@Test

public void intDivision_nonZeroDivisor_success() throws Exception {

assertEquals(2, new IntPair(4, 2).intDivision());

assertEquals(0, new IntPair(1, 2).intDivision());

assertEquals(0, new IntPair(0, 5).intDivision());

}

@Test

public void intDivision_zeroDivisor_exceptionThrown() {

try {

assertEquals(0, new IntPair(1, 0).intDivision());

fail(); // the test should not reach this line

} catch (Exception e) {

assertEquals("Divisor is zero", e.getMessage());

}

}

}

Notes:

- Each test method is marked with a

@Testannotation. - Tests use

Assert.assertEquals(expected, actual)methods to compare the expected output with the actual output. If they do not match, the test will fail. JUnit comes with other similar methods such asAssert.assertNullandAssert.assertTrue. - Java code normally use camelCase for method names e.g.,

testStringConversionbut when writing test methods, sometimes another convention is used:whatIsBeingTested_descriptionOfTestInputs_expectedOutcomee.g.,intDivision_zeroDivisor_exceptionThrown - There are several ways to verify the code throws the correct exception. The third test method in the example above shows one of the simpler methods. If the exception is thrown, it will be caught and further verified inside the

catchblock. But if it is not thrown as expected, the test will reachAssert.fail()line and will fail as a result. - The easiest way to run JUnit tests is to do it via the IDE. For example, in Intellij you can right-click the folder containing test classes and choose 'Run all tests...'

Adding JUnit 5 to your IntelliJ Project -- by Kevintroko@YouTube

Resources

- JUnit Official User Guide

- JUnit 5 Tutorial – Common Annotations With Examples - a short tutorial

- How to test private methods in Java? [ short answer ] [ long answer ]

Can use intermediate features of JUnit

Skim through the JUnit 5 User Guide to see what advanced techniques are available. If applicable, feel free to adopt them.